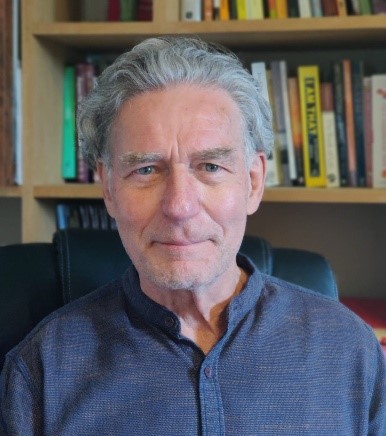

Michael West, Professor of Organisational Psychology at Lancaster University, explains why humans are compassionate beings and why this should play a key role for managers in the healthcare sector.

Interview: Dietmar Schobel

HEALTHY EUROPE

Professor West, what is “compassionate leadership”?

Michael West: Compassion is a core element of who we are. We humans are designed to feel compassion – not only for others, but for ourselves too. When we behave compassionately and support others, the reward centres in our brain are activated. You could also say: we are hard-wired to help others in pain. Leadership that incorporates compassion manifests itself in four behaviours: attending, understanding, empathising and helping.

HEALTHY EUROPE

How does a compassionate leader behave in practice?

Michael West: To be attending means being present with and focusing on others. It stands for “listening with fascination”, as communication trainer Nancy Kline put it. Being a good listener is probably the most important leadership skill. Compassionate leaders take the time to hear about the challenges, obstacles, frustrations and harm experienced by their colleagues. And they also listen to what they relate about their successes and what they enjoy about their work. Understanding involves taking time to properly explore the situations people are struggling with. It implies valuing and exploring conflicting perspectives rather than leaders simply imposing their own understanding. Empathising means to mirror and feel colleagues’ emotions like distress, frustration, or joy, without being overwhelmed and becoming unable to help. Helping involves taking thoughtful and intelligent action to support individuals and teams. Compassionate leaders remove obstacles that get in the way of people doing their work, whether it is a matter of chronic excessive workloads, conflicts between departments or something else. Compassionate leadership not only means being empathetic, but actually helping and supporting wherever necessary too.

Effective organisations typically have only two or three reporting levels.

MICHAEL WEST, PROFESSOR OF ORGANISATIONAL PSYCHOLOGY AT LANCASTER UNIVERSITY

HEALTHY EUROPE

Time pressure has increased across all industries in recent years – and in the healthcare and welfare systems in particular. Is it even possible to implement a concept like “compassionate leadership” under these circumstances?

Michael West: Not only is it possible, but it’s urgently needed especially in the healthcare and welfare systems that are struggling with growing staff shortages. The most crucial task at the moment is to curb the outflow of healthcare workers. We have seen when implementing the concept of compassionate leadership in practice that it significantly increases both job satisfaction among the staff and also the quality of patient care, and it ultimately proves to be economically beneficial. This has been confirmed by numerous studies. There is also evidence that in organisations where there is room for compassion and time for listening, workdays are on no account spent less efficiently. In most cases, the opposite is true. In fact, the concept of compassionate leadership is especially well suited to the healthcare and welfare sector, because the percentage of employees who chose their profession in order to help others is very high in this area.

HEALTHY EUROPE

Where is the concept of compassionate leadership already being implemented?

Michael West: It is already being implemented in numerous healthcare facilities in England, Ireland and other European countries. One example is Wales, where we are currently working in collaboration with Health Education and Improvement Wales to train all managers in the Welsh healthcare system. Another example is the Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, which has around 5,000 staff and provides mental and physical health services in the county of Berkshire in England and has likewise adopted the concept of compassionate leadership. Surveys have shown that the stress levels of employees and the staff churn rate there are the lowest in England, while job commitment is especially high.

HEALTHY EUROPE

What effect does compassionate leadership have on organisations as a whole?

Michael West: It affects what leaders pay attention to, what they monitor, what they reward, what they talk about, what they communicate to staff, and what is valued in the organisation. Compassionate leadership enhances the intrinsic motivation of staff and reinforces their fundamental altruism. It helps promote a culture of learning where risk taking is accepted within safe boundaries, and where there’s an acceptance that not all innovation will be successful. It is diametrically opposite to cultures of blame and fear and bullying. Compassion also creates psychological safety, and thus enables staff to feel safe to raise concerns about errors, near misses, and problems that they perceive in the workplace. So, leadership behaviour ultimately affects the organisational culture as a whole. This doesn’t just concern interactions between the employees, but also those with the patients, their relatives and everyone else who has dealings with the healthcare facility in question.

HEALTHY EUROPE

Interaction on equal terms is obviously a central element of compassionate leadership. How compatible is this with the hierarchical structures of many large organisations, which are often particularly pronounced in the healthcare sector?

Michael West: In large healthcare organisations, there are indeed usually ten and more levels of hierarchy. That said, we know that effective organisations typically have only two or three reporting levels. This means we have to move away from rigid hierarchical structures. That’s not the way to manage highly motivated people. Instead, we should empower employees to make more decisions autonomously and expand their freedom to do so. Fundamental changes in organisational structures will be necessary in order to achieve this. Currently, we are seeing that several healthcare institutions and systems are taking the first steps in the right direction.

PROFILE

Michael West was born in 1951 in Loughborough, England. He grew up in Wales and studied psychology at the University of Wales where he also completed a PhD dissertation on “Psychophysiological and Psychological Correlates of Meditation” in 1977. “Meditating means being in the here and now effortlessly,” explains the British psychologist, who has been exploring the subject since his first year at university and has learned a number of different meditation techniques. After his studies, he worked in a coal mine for a year. He remarks: “It was there that I learned the true importance of teamwork. Having great trust in one another is a precondition for working in the mines.” Mutual support, trust and teamwork are all principles that have been central to his academic career as well, as a professor of organisational psychology at Lancaster University and additionally the author and co-author of 20 books and over 200 scholarly articles. Michael West developed the concept of “compassionate leadership”, which he continues to introduce to many large national and international organisations. During his four years as Executive Dean of Aston Business School, when he was responsible for 200 employees, he implemented the idea himself: “It is all about creating an atmosphere in which employees are recognised, supported, and valued. If that is successful, you are ultimately redundant as a manager.” Michael West is married to a clinical psychologist; he has four children and also five grandchildren aged between two months and two years.